The Buffett Indicator Home Page

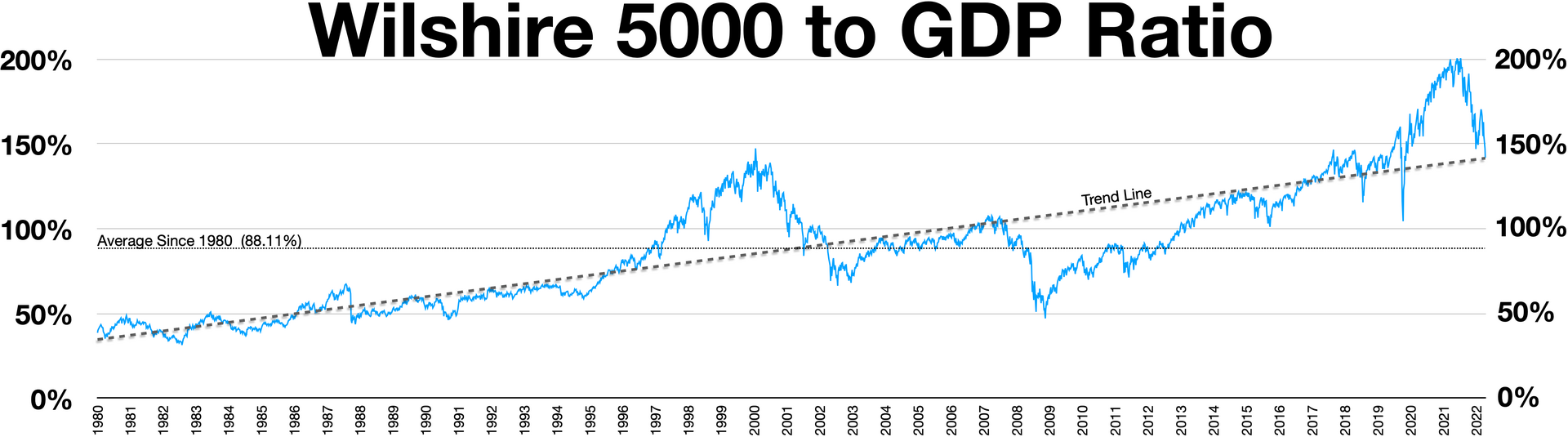

Buffett Indicator: 222.99%

Total Market Cap: 69,338.87

GDP: 31,095.09

What is the Buffett Indicator?

The Buffett Indicator is a financial metric that compares the total value of all publicly traded stocks in a country to that country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Named after Warren Buffett, one of the world’s most successful investors, the indicator is often used as a broad measure of market valuation.

The Buffett Indicator, also known as the Market Capitalization-to-GDP ratio, is a valuation tool used to determine whether the overall stock market is overvalued or undervalued at a specific time. Warren Buffett introduced this metric in 2001, describing it as “probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment.” In its current form, the indicator compares the market capitalization of the U.S. Wilshire 5000 index to the country’s GDP. This metric is closely monitored by the financial media as a key measure of U.S. market valuation, both in its absolute form and when adjusted for long-term trends.

How the Buffett Indicator Works

Why is the Buffett Indicator Important?

Limitations of the Buffett Indicator

Buffett acknowledged that his metric was a simple one and thus had “limitations,” yet the theoretical foundation of the indicator, particularly for the U.S. market, is widely regarded as sound.

For instance, studies have demonstrated a strong and consistent annual correlation between U.S. GDP growth and the growth of U.S. corporate profits, a relationship that has become even more pronounced since the Great Recession of 2007–2009. GDP effectively captures scenarios where certain industries experience significant margin increases while accounting for reduced wages and costs that may compress margins in other sectors.

While the Buffett Indicator has been calculated for many international stock markets, it comes with caveats. Other markets often have less stable compositions of publicly listed companies (e.g., Saudi Arabia’s metric was significantly impacted by the 2018 listing of Aramco) or vastly different ratios of private to public firms (e.g., Germany vs. Switzerland). As a result, using the indicator for cross-market comparisons of valuation is generally not advisable.

History

Buffett explained that for the annual return on U.S. securities to significantly outpace the annual growth of U.S. GNP over an extended period: “you would need the line to go straight off the top of the chart. That won’t happen.” He concluded the essay by indicating the thresholds he considered indicative of favorable or risky times to invest: “If the percentage falls to the 70% or 80% range, buying stocks is likely to work out very well. If the ratio nears 200%—as it did in 1999 and part of 2000—you are playing with fire.”

Since then, Buffett’s metric has been widely recognized as the “Buffett Indicator” and continues to garner significant attention in the financial media and modern finance textbooks.

Recent Trends

There is evidence that the Buffett Indicator has generally trended upwards, particularly since 1995.